The primary co-dependency issue for the financial professional involves falling into the abyss of only feeling worthy, happy, righteous, and confident if one’s production—generally, the amount of commission/bonus/”slice of the pie”—is at least adequate, and supports his desired lifestyle.

The primary co-dependency issue for the financial professional involves falling into the abyss of only feeling worthy, happy, righteous, and confident if one’s production—generally, the amount of commission/bonus/”slice of the pie”—is at least adequate, and supports his desired lifestyle.

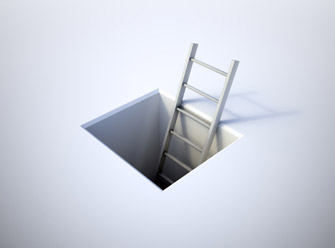

This is the inherent occupational hazard, or trap, for the financial professional: feeling that his sense of self-worth, his value as a human being, and his happiness are all dependent on what can sometimes actually be an unrealistic level of production. Not all FPs are equally talented, hardworking, or “lucky.”

A certain amount of fear and anxiety can be inspiring—but more often, when the desired level of production is not met, the financial professional experiences excessive fear and sometimes even panic, which erodes judgment, decreases cognitive capacity, limits motivation, and of course performance suffers.

This is especially common in this era of feudal-like corporate cultures, wherein one’s production numbers dictate one’s office placement and even the number of windows in the office and where the windows face, number of assistants, and other perks.

The financial professional may start in the workplace as an intern or lowly account representative—a fief—and in time can end up as a senior vice president—a lord—thanks to his production numbers alone. This is because production dictates status, and the square footage of one’s office space, number of assistants, title, access to special meetings and cliques within the company—and these traditions contribute to the elitist, feudal, hierarchical measurements of your worth.

In most financial firms, production dictates all, from the number of windows in your office to its vantage point in the corporate space. And then, of course, these evident terms of existence can begin to creep into your own personal sense of your soul and self, wreaking havoc on your self-esteem.

Many financial professionals come from middle and working class backgrounds; working in the financial world gives them a leg up with access to wealth and status. Many of these workers are sales-oriented types, planners, gamblers in a more civilized form—even social climbers, overachievers, and materialists who innately equate their worth as a human to the numbers on their balance sheets, and the amount of money they have under management.

They can also be charming, seductive, manipulative, and charismatic. Generally they revere money and power; they know they have landed in a field in which they can make much more money than they would in most other industries, and have a certain cache—in fact, some of them know this first-hand, because they are converts: former teachers or sales administrators.

Their natural talents permit them to excel in an industry that traditionally offers very little training or experience, but in return they have to accept the job’s high-risk nature.

Yet, because they are so dependent on production to validate their self-worth, they are forever lashed to the mast of a vessel that must ride out storms, bubbles, and panics.