No blog that breaches the subjects at the intersection of economics and psychology, especially wall street psychology, would be complete without some discussion of Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Hayek, and Milton Friedman. These scholars laid the groundwork for modern thinking about commerce, money theory, credit/debt, the business cycle, production, government intervention, and economics.

No blog that breaches the subjects at the intersection of economics and psychology, especially wall street psychology, would be complete without some discussion of Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Hayek, and Milton Friedman. These scholars laid the groundwork for modern thinking about commerce, money theory, credit/debt, the business cycle, production, government intervention, and economics.

Adam Smith (1723-1790), a philosopher and Scotsman is considered the founder of modern economic theory. Smith had infinite faith in humanity; he believed that people would act in their own self-interest and produce the goods and services required by society as a whole. Somewhat of a poet, Smith contended that an invisible hand was the mechanism behind self-regulation. His magnum opus, “The Wealth of Nations,” was published in the year of our independence, 1776. Smith felt that a free market economy could run on its own steam on auto pilot. Smith’s key concept supported a laissez-faire attitude (the French term literally means “let go,” as in leave it be) by the powers that be, the government, though Smith never actually used that term. In essence he felt that the markets would take care of themselves, and he believed in harmony and growth. He was an outspoken opponent of government intervention, product regulation, trade restrictions, and labor laws. The metaphor of the invisible hand, also known as the invisible hand of the market, is a fascinating concept which Smith perceived of as the self-regulating nature of the marketplace which he discussed in his “Theory of Moral Sentiments.” Smith’s invisible hand was the simultaneous occurrence of the forces of self-interest, competition, and supply and demand which he felt would be inherently capable of allocating resources in society. Not to worry.

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), however, felt quite differently. He advocated interventionist economic policy encouraging governments to leverage fiscal and monetary policies to allay the adverse consequences of downturns in business cycles, economic recessions, and depressions. Keynes argued that decisions made by individuals and groups in the private sector can, at times, produce negative macroeconomic results which can be mitigated by monetary measures and policy actions in the public sector. Whereas classical economists argue the validity of Say’s Law, that “supply creates its own demand,” as a market mechanism to avoid a “general glut,” Keynes contended that collective demand for goods might be deficient in times of economic crisis fueling high unemployment and damaging output (production). Hence, Keynes asserted that government policies should be applied to enhance the aggregate demand thereby stimulating economic growth and in turn decreasing unemployment and deflation. Keynesian strategies for recovering from a depression, or a “great recession,” involved stimulating the economy advocating reduction on interest rates and government investment in infrastructure. Big Daddy to the rescue.

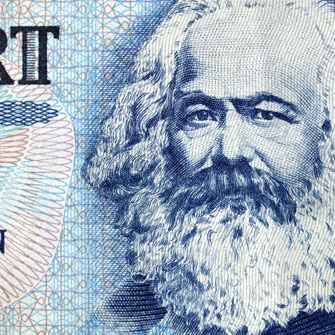

Karl Marx (1818-1883), the founder of modern communism, provides us with a completely different perspective. Marx merges politics and economics. He contended that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” He argued that capitalism would produce internal tensions which would lead to its destruction. Just as capitalism replaced feudalism, Marx believed that socialism would in turn replace capitalism and lead to a stateless, classless society he referred to as pure communism. He theorized that this end result would emerge after a transitional period called the dictatorship of the proletariat; a period referred to as the “worker’s state, or the worker’s democracy.” As an historical materialist, Marx contended that society rises and falls in conjunction with how much it impedes human productive power. He believed in the labor theory of value which was determined by the socially necessary time for production. Surplus value went to the owners of production, and not to the workers. Marx asserted that workers should own part of production since they were an integral part of the means of production itself. In a sense, he foreshadowed profit sharing and, ultimately, worker safety standards. What about incentive, individual differences, and investment entitlements?

Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), a Nobel Prize winning economist, was a leading figure in the Austrian School of Political Economy. Unlike his predecessors, Hayek was more of a multi-disciplinary thinker. He was an advocate for classical liberalism and free market capitalism. He believed in limited government, due process and the rule of law, constitutionalism, and individual liberties: free markets, freedom of speech, press, assembly and religion. He considered private property rights essential to the sovereignty of the individual. He did not approve of socialism and collectivism. His classic work, “The Road to Serfdom” cogently documents his thinking. Hayek identified two traditions within classical liberalism: the British model and the French model. The British believed in empiricism and common law whereas the French focused on rationalism and the “unlimited powers of reason.” As a political economist Hayek saw utility as a foundation for public policy. Hayek contended that government had a role in the management of the economy in terms of a monetary system, proper flow of information, and regulation of worker hours and safety. He advocated for Free Banking with the proviso that banks experiment and innovate in order to find the best methods for doing business. He believed in spontaneous order. His later work concentrated on business cycle theory, and theories of money and credit. He was not a supporter of artificially low interest rates asserting that they would only spur inflation in the future. Hayek was able to interweave social and political philosophy, psychology, economics, law, and the philosophy of science in novel, multidimensional ways. One might say he had “cognitive holographic tendencies.” His work was pithy and deep across many disciplines. He seemed to also possess an innate understanding of how people’s thinking and money behavior could be shaped by economic and political conditions on personal (micro) levels and on government (macro) levels.

Milton Friedman (1912-2006), a Nobel Prize winning economist, specialized in consumption theory, monetary policy, and stabilization policy. Early in his career he was a Keynesian, but he never advocated wage and price controls. In fact, he has been called the first counterrevolutionary against Keynesianism. He endorsed a macroeconomic policy which became known as monetarism. He believed in a natural rate of unemployment which governments could modulate at the risk of inflation. He objected to a good deal of government regulation, and favored free market economics. In his seminal work, “Capitalism and Freedom,” he called for floating exchange rates, a voluntary military, negative income tax, education vouchers, and abolition of medical licenses!

This cursory examination of “The Fab Five,” a select group of economic theorists, can provide the financial professional with an initial template upon which to expand perspectives in terms of how money, markets, economies, and production actually work. The FP’s willingness to study economic theory, money behavior, and wall street psychology will only enhance their financial planning and decision making skills in this most challenging business. And help them make sense out of the money-mad world in which they live and work!